Campylobacter infections in Scotland

Campylobacter infections in Scotland

The main routes and reasons for the increase in Campylobacter infection in Scotland

November 13, 2017

Campylobacter infections are the primary cause of bacterial gastroenteritis in the developed world. The typical symptoms are vomiting, nausea and diarrhoea. Symptoms tend to come on within two to five days of eating the contaminated food or of being in contact with a contaminated animal. The number of cases has increased over the last ten years and in some parts of the world, such as Asia and the Middle East, campylobacteriosis is endemic. The economic burden of these infections is high and in the UK, Campylobacter infections cost an estimated £900 million each year.

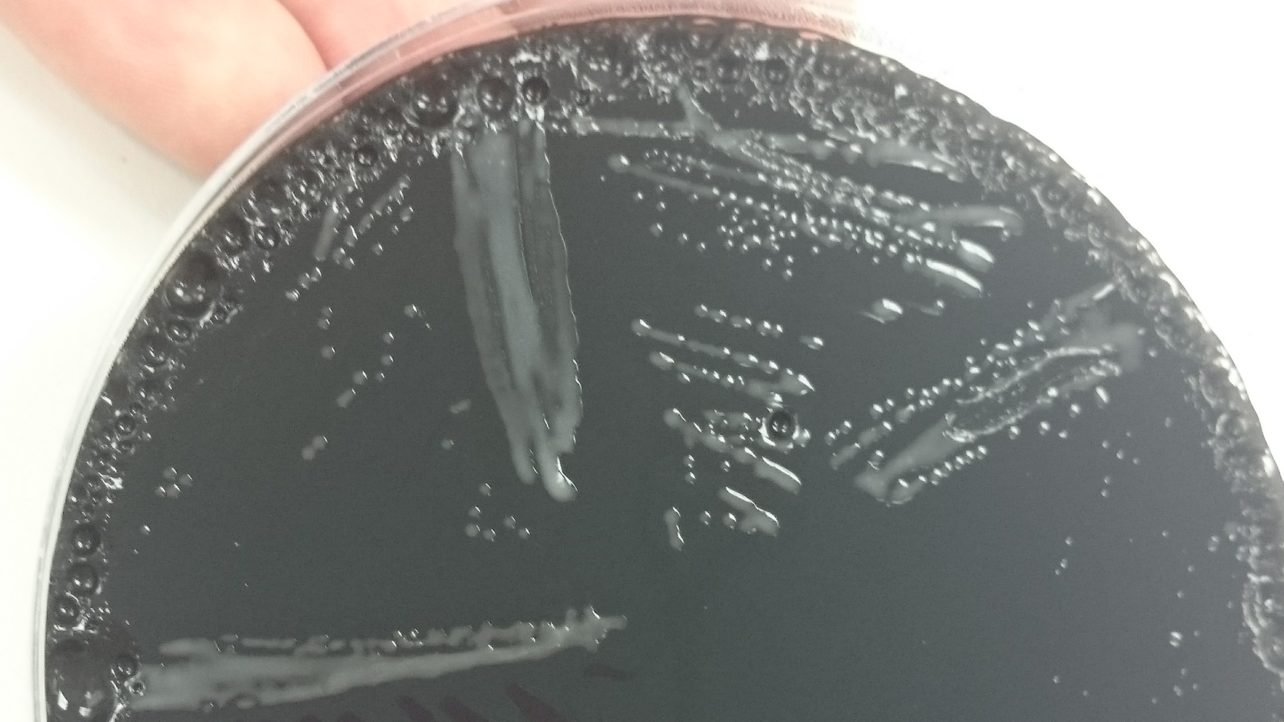

Campylobacter jejuni is the most common cause of campylobacteriosis, with C. coli accounting for only 10% of annual reported cases in the UK. The majority of Campylobacter infections affect young adults and children and most cases are sporadic, outbreaks are rare. Infections are thought to result from the consumption of contaminated meat, water, poultry and contact with animals contaminated with the bacteria. Food-borne causes of infections such as consumption of contaminated chicken is the primary route of Campylobacter infection, however, as the sources of most reported incidences is unknown or difficult to determine, this cannot be confirmed.

Data gathered by Health Protection Scotland (HPS), showed that there has been a marked increase in Scotland of reported Campylobacter infections over the last ten years. In 2009, reported incidences rose by 30% and have remained so, the reasons for the increase still remain unclear.

Research by Sheppard et al. (2009) predicted that the biggest reductions in Campylobacter infection incidences in Scotland will come from interventions aimed at the poultry industry and this is where most of the reduction strategies are based. A microbiological survey of fresh, UK produced chicken found that Campylobacter was present in over 70% of the 4011 samples tested which means that most of the chicken you buy in the supermarket will contain Campylobacter.

One of the strategies highlighted by Health Protection Scotland and Food Standards Scotland is to raise public awareness of Campylobacter infections and more specifically food preparation and hygiene principals to safeguard the Scottish population from higher risk of infection. Data gathered by the Food Standards Agency in 2010, found that there was a need for more education and awareness. It would be beneficial for a follow up survey to identify whether educational campaigns since 2009-2010 have changed hygiene practices and increased awareness of Campylobacter. Do people know what Campylobacter is and how their cooking and kitchen hygiene practices can limit the spread of bacteria already present in their raw food? Cooking practices such as washing chicken, is something that has been passed down through generations and it is only now that educational campaigns are warning us against it. Washing chicken before cooking can spread harmful bacteria around the kitchen, it is best to limit contact with the raw food and wash hands and other surfaces thoroughly with soap if contact does occur. Campylobacter has a low infective dose, meaning that only a small amount of the pathogen can render you seriously ill, it is worth taking the extra care and attention to protect you and your family.

Despite significant efforts by the government and industry, the strategies they have focussed their attention on such as poultry farm interventions, have failed to lower the incidences of Campylobacter infections. The most recent data from Health Protection Scotland in 2015 shows that there has been no significant reduction of incidences. Perhaps targeting efforts on increasing public awareness of Campylobacter, specifically cooking and hygiene practices, have a greater effect on bringing these numbers down.

Please click on Campylobacter testing for more information on the testing that Express Micro Science can perform on food products.

Article written by Laura Cameron, Express Micro Science microbiologist and studying for an MSc in Infection Prevention and Control. Laura will be starting a PhD at Glasgow University shortly.